- Home

- Angela Huth

Land Girls Page 5

Land Girls Read online

Page 5

Prue came to an almost entirely black cow, Felicity. She had particularly intelligent and gentle eyes, surrounded by long blueish eyelashes. Prue wondered what they would look like with mascara, and smiled to herself. She glanced down at the swollen pink udder, with its obscene marbling of raised veins. She ran a finger the whole length of Felicity’s spine, the wrong way, so that the cow’s black hair was forced up over the bone.

‘I like you,’ she said aloud.

She raised her eyes above the animal’s spine and found herself looking into the hooded eyes of the man she assumed was Joe. Cor! He was quite something … Her mind flicked through the handsome film stars she had dreamed of, but could come up with no one comparable. Anyway, she quickly decided, she’d be happy to sacrifice ploughing, and milk the whole herd morning and night if this Joe was to be her supervisor. His eyes shifted, expressionless, a bit spooky, to her hair, the bow. Funny how she’d been impervious to everybody else’s opinion, but there was something about Joe’s look that made her feel a bit foolish. The one thing she did not want was instant disapproval. That would start them off on the wrong foot.

‘Why’s she called Felicity, this one?’ she asked at last, head on one side, coquettish – a gesture she had learned from Veronica Lake.

‘She was a happy calf. She’s a happy cow.’ Joe slapped Felicity on the rump. He seemed to have forgotten about the bow.

‘Can I start on her?’

‘No. We start at the other end with Jemima.’

Prue pouted. ‘I’m Prue, by the way. Your father calls me Prudence.’

‘I know. How’s your milking?’

‘Just the few weeks on the training course. I’m not bad.’

‘Gather you’re keen to get on the tractor.’

‘I said that, just in case Mr Lawrence had any ideas about women not liking ploughing. I’m quite happy to milk.’

‘Rather enjoy it myself. A lot of farms have gone over to machines. Isn’t really worth it for a herd of our size, though Dad was talking about it before this bloody interruption.’ They both listened to the noise of a small aircraft squealing overhead. Joe pointed to the far end of the shed. ‘There are a couple I haven’t washed down – Sylvia and Rose. Mop, bucket and towels through there. Rule here is that we change the water every two cows. Stool and milking bucket in the dairy. I’ll show you how to put on the cooling machine when we’ve finished.’

‘Don’t worry. I understand about cooling machines,’ said Prue. She managed to sound as if her understanding went far beyond mere technicalities.

‘We should get going. I’m running late this morning, seeing to your friend.’

‘I’ll make a start.’

Prue blushed with annoyance: to think that Ag, asked merely to sweep the yard, had been the first to engage Joe’s attention. She moved slowly down the concrete avenue that divided the two rows of cows’ backsides, swinging her hips. Joe’s eyes, she knew, were still on her. She picked up the mop and bucket with the calculated flourish of a star performer, and began to swab Sylvia’s bulging udder as if the job was a movement in a dance. When she had finished washing both cows, she sauntered back to where Joe was milking a restless creature called Mary.

‘And where,’ she asked, hand on one hip, provocative as she could manage in her given surroundings, ‘might I find a cup for the fore milk?’

Joe released Mary’s teats. He looked up at Prue, impassive. ‘I don’t believe we have one,’ he said.

‘Don’t have one?’ Prue’s voice was mock amazed. ‘We were taught it was essential—’

‘Dare say you were. We don’t do everything by the book, here. We just draw off the first few threads before starting with the bucket.’ He turned back to his milking.

‘On to the floor? Do you suppose,’ said Prue, after a few moments of listening to the rhythmic swish of Mary’s milk hitting the bucket, ‘this is a matter I should bring up with your father? Or the district commissioner? Or—?’

‘Bring it up with who you bloody like,’ said Joe. Although his face was half-obscured by Mary’s flank, Prue could see he was smiling.

In the dairy, she washed her hands with carbolic soap in the basin. She was aware of a small triumph, a feeling that some mutual challenge had been recognized. If nothing else, a teasing game could be played with Joe. That would give an edge to the boring old farm jobs – and who knows? One game leads to another …

Astride the small milking stool, head buried in Jemima’s side, hands working expertly on the hard cold teats, Prue allowed herself the thrill of daydreams. Surprisingly, she was enjoying herself. She liked the peaceful noises – muted stamp of hooves, and chink of neck chains – that accompanied the treble notes as jets of milk sizzled against metal bucket. She was aware that the sweet, hay smell of cow breath obliterated her own Nuits de Paris – she would tell Mr Lawrence, at the right moment, he need have no fears. The thought of the hugeness of Joe’s boots made her feel at home, somehow – which was an odd thought considering this chilly milking parlour was as far away from her mother’s front parlour as you could get. She found herself praying that milking would be her regular job, if Joe was to be her milking partner. But her mind was diverted from imagining the many possibilities of this partnership by the distant sound of rattling marbles. She stiffened.

‘Miles away,’ shouted Joe. Just practice, by the sound of it.’

Prue waited tensely for a few moments, fingers slack on the teats. She had forgotten the war. She stood up, easily lifted the bucket of foamy milk. It smelt faintly of cowslips. Beaten Joe to it, she saw with pleasure. It was tempting to point out to him what a quick milker she was. But Prue decided against this. She went to the dairy, sloshed the milk into the cooling machine and chose a bucket from the sterilizing tank for the next cow. She had had her one small victory this morning. That was enough to begin with.

Stella, when she saw her ‘cow’, laughed out loud. It was a crude, ingenious device: a frame made of four legs, inward sloping, like the legs of a trestle table. From its top was slung a canvas bag roughly shaped like an udder and from which dangled four rubber teats the pink of gladioli. It reminded Stella of a pantomime cow.

‘Oh Mr Lawrence,’ she said, ‘is this to be my apprenticeship?’

‘Won’t take long. You’ll soon get used to it.’

Mr Lawrence gave her one of his curt smiles. He picked up a bucket of yesterday’s milk and poured it into the bag. Then he squatted down on the stool drawn up to the ersatz udder, placed the bucket beneath the empty bag, and took a teat in the fingers of both hands.

He was no expert, and was aware of the ridiculous picture he made. His fingers were curiously shaky. A feeble string of milk trickled from the teat.

‘Easier on a real cow,’ he said. ‘Here, you have a go.’

Stella took his place, held the smooth pink teat.

‘It’s a rhythm you want to aim for,’ he explained, when he had watched her for a while. ‘Once you’ve got the rhythm, you’re there, and the cow’s happy. That’s it, that’s a girl.’ The farmer moved proudly back from his pupil. She was bright, this one, as well as attractive. ‘Fill the bucket a couple of times, and you can be on to the real thing tomorrow. All right?’

‘Fine.’

Mr Lawrence allowed himself a few moments in silent appraisal. Funny girl. So formal in her speech, and yet so quick. He let his eyes rest on her back, the pretty hair tumbling forwards. Where it parted he could see a small patch of her neck, no bigger than a man’s thumbprint. With all his being he wanted to touch it, just touch it for an infinitesimal moment, feel its warmth. As he stood there, fighting his appalling desire, his hands and knees began to shake. Dizziness confused his head. Stella’s voice came from a long way off.

‘Am I doing all right, d’you think?’

It was several moments – silence rasped by the silly sound of the squirting milk – before he dared answer. ‘You’re doing fine.’

He took a step towards her, watched hi

s hand leave his side, stretch out to her innocent back: hover, quiver, withdraw.

Stella turned, smiling. She saw what she thought was a look of deep misgiving in Mr Lawrence’s eyes. The shyness of the man! It must be dreadful, she thought, to find the peace of Hallows Farm suddenly disrupted by unskilled girls from other worlds. Sympathy engulfed her, but she could think of no appropriate words with which to convey her feelings.

‘I’ll be back in a while,’ Mr Lawrence said. He waited till Stella returned to concentrate on the rubber teats, and quickly left the shed.

Alone, Stella sniffed the sour milk and manure smell of the shed. It was cold, damp. Her fingers on the teats were turning mauve. She determined to get her peculiar training over as fast as possible, and concentrated on the rhythmic massage of the ludicrous teats. At the same time she began to compose the funny letter she would write to Philip tonight: my first day a land girl – with a rubber cow. This prompted the thought of the post. Philip had promised to write immediately. She ached to hear from him. The two hours till breakfast, when she could ask about the delivery of letters, seemed an eternity. In some desolation, Stella looked down at the thin covering of milk on the bottom of the bucket.

Two hours later, shoulders and legs stiff from the awkward position (it would be much more comfortable with a real cow to lean against), Stella rose and stretched, her apprenticeship, she hoped, over. She had filled the bucket twice and felt like a qualified milker. Once she had got the hang of it – the rhythm, as Mr Lawrence had said – it had been quite easy. Behind the gentle splish-splash of the milk she had dreamed of Philip, going over in her mind every detail of the few occasions on which they had met. And when she swooped back to the present, she saw the humour of her situation – the adrenalin of being in love making bearable the milking of an imitation cow.

Now, she leaned over the bottom half of the shed door, looked out on to the yard. The Friesians were ambling towards the gate. They took turns to enjoy the distractions of familiar sights. Sometimes one would pause to give a bellow, puffing silver bells of breath into the sharp sunny air. Stella understood their lack of concentration, and smiled at the sight of Prue and Ag urging them on, with the occasional tentative whack of a stick. Prue’s pink bow had lost some of its former buoyancy but still fluttered among her blonde curls like a small demented bird. She bounced and jiggled and enjoyed shouting bossily to the cows. In contrast, Ag walked with large dignified strides, never raising her voice. There was something both peaceful and wistful in her face. Stella felt drawn to this girl, wondered about her.

The last cow left the yard. At that moment two men came out of the barn. Stella assumed the tall one to be Joe, and recognized at once the shape of the man she had seen last night. His hand was on the shoulder of the much older man who wore thickly corrugated breeches and highly polished lace-up boots, the uniform of grooms before the last war. Joe seemed to be trying to persuade the old man of something, and was meeting resistance. On their way across the yard, Joe looked up and spotted Stella.

‘Breakfast,’ he shouted, but did not wait for her.

The idea of breakfast reminded Stella of her hunger. But reluctant to go into the kitchen alone, she made her way down the lane to meet the others returning from the meadow. They, too, declared their hunger. All three compared stiff joints and cold fingers, and hurried back to the farmhouse.

By the time they reached the kitchen the three men were already half-way through huge plates of bread, bacon, eggs, tomatoes and black pudding. Mrs Lawrence was shifting half a dozen more eggs in a pan at the stove. She wore the same faded cross-over pinafore as yesterday, which hid all but the matted brown wool of the sleeves of her jersey. There was something extraordinarily detached, but reassuring, in her back view, thought Ag. It was as if the outer woman was performing her chores, while an independent imagination also existed to power her through the mundane matters of daily life.

Mr Lawrence introduced Ratty to the girls, remembering all their names, having checked with his wife. Ratty, a man of economy in his acknowledgements, made his single nod in their direction extend to all three of them. In that brief moment of looking up, Ag observed his extraordinary eyes, grained with all the colours of a guinea fowl’s breast. Here was a man who would provide much material for her diary, she felt, as she sat beside him, unafraid of his distinctive silence. Prue took her chance to sit next to Joe. Mr Lawrence observed her choice with a hard, flat look.

‘Well, we got through that all right, I’d say, didn’t we, Joe?’ Prue turned to the others. ‘I did twelve cows, Joe did the other eight. Just think, only a few more hours to go and we start all over again, don’t we, Joe?’

Joe shook his head. ‘Not me. Dad’s on the afternoon milk.’

Prue’s face fell. She accepted the plate of fried things from Mrs Lawrence and concentrated on eating.

Mr Lawrence, finishing first, seemed eager to be away. He outlined the chores for the rest of the morning. Ag was to help Mrs Lawrence with the henhouse, and try to patch up the tarpaulin roof. Prue was to sluice down the cowshed, sterilize the buckets, scour the dairy, and put the milk churns into the yard. ‘Ready,’ he added, ‘for the cart. Think you’ll manage to get them on to the cart, Prudence?’

Prue looked up from her eggs, alarmed, knowing what a churn full of milk must weigh. But she had no intention of looking feeble in Joe’s eyes. ‘Of course,’ she said.

‘I mean, you’re at least a foot taller than a churn, aren’t you?’ Mr Lawrence’s fragment of a smile indicated he was enjoying his joke.

Now he turned to his left, where Stella swabbed up egg yolk with a fat slice of bread. ‘Know anything about horses?’

‘A little.’

‘Then you can come with me. We’ll walk down to Long Meadow, give you an idea of the lie of the land.’

The three men rose, leaving their empty plates and mugs on the table. Mrs Lawrence sat down at last, with a boiled egg. Her cheeks were threadbare in the brightness, caverns of brown fatigue under both eyes. She cracked the egg briskly, looked round at the girls.

‘You’ll get used to it,’ was all she said.

By the end of their first day, the land girls were exhausted. After four o’clock mugs of tea, they lay on their beds, trying to recover their energy for supper.

If we’re this fagged, what must poor Mrs Lawrence be?’ asked Ag. ‘Up before us, never a moment off her feet. And now cooking. Perhaps we should go down and help.’

‘Couldn’t,’ sighed Prue. ‘Twenty-four cows milked dry first day – ninety-six teats non-stop, you realize? That’s me for day one. Finished.’

None of them moved, despite the guilty thought.

‘We should be less stiff in a week or so,’ said Ag, rubbing a painful shoulder, ‘able to do more.’

‘More?’ giggled Prue. ‘We’re land girls, not slaves, I’ll have you know.’

‘I liked the day,’ said Stella, sleepy. ‘I liked the walk to get Noble, and then getting into a terrible muddle with the harness.’

‘Mr Lawrence can’t keep his eyes off you,’ said Prue, after a while.

‘What?’

‘Haven’t you noticed?’

‘Don’t be daft.’

Ag laughed. ‘Your imagination, Prue,’ she said, from her end of the room. ‘I think Mr Lawrence is so giddied by our presence he doesn’t know where to look. He’s not used to women on the farm, or anywhere. But you can tell about him and Mrs Lawrence: soldered for life, I’d say. They don’t have to speak, or even look. They’re bound by the kind of wordless understanding that comes from years of happy marriage. My parents were like that, apparently.’

Prue sat up. She pulled the pink bow from her hair. ‘Don’t know about all that,’ she said. ‘My mum and dad love each other no end, but they don’t half scream at each other night and day. Do you think we stay in these things for supper? I bloody stink. Cow, manure, Dettol – you name it, I reek of it. As for my nails …’ She looked down at her hands. ‘Wha

t are we going to do about our nails?’

‘Give up,’ said Stella, smiling.

‘Not bloody likely. Land girl or not, I’m going to keep my nails, any road. Anyhow, what did you two think of him?’

‘Who?’ asked Ag.

‘Joe, of course.’

‘Seems nice enough. Shy.’

‘Nice enough? Are you blind? Don’t you recognize a real smasher when you see one? He’s something, Joe, don’t you realize, quite out of the ordinary? No easy fish, I reckon, but I’ll take a bet. Joe Lawrence and I won’t be too long before we make it.’

She looked from Stella to Ag, trying to read their reactions.

‘There’s Janet,’ Ag said at last, ‘isn’t there?’

Prue giggled. ‘Janet? Did you take a look at her photo? She’s not what I’d call opposition.’

‘But they’re engaged,’ said Stella.

‘Long time till the spring.’ Prue continued to study her nails. ‘Anyhow, I’ll keep you in touch with progress, if you’re interested.’

‘Immoral,’ said Ag, half-smiling.

‘Are you shocked?’

‘Rather.’

‘All’s fair in love and war’s my motto. And this is a war, remember? Don’t know about you two, but I’m getting out of these stinking breeches. Green skirt, pink jersey, lashings of Nuits de Paris, whatever Mr Lawrence says, and Joe’ll be beside himself, you’ll see.’

While the other two laughed, Prue took a shocking-pink lipstick from a drawstring bag and concentrated on a seductive outline of her mouth. ‘I’ve never gone for anyone so huge. What do you bet me?’ She challenged Stella, the most likely to take on the bet. But Stella’s mind had wandered far from Joe.

Sun Child

Sun Child South of the Lights

South of the Lights Virginia Fly is Drowning

Virginia Fly is Drowning Of Love and Slaughter

Of Love and Slaughter Such Visitors

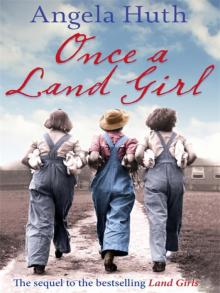

Such Visitors Once a Land Girl

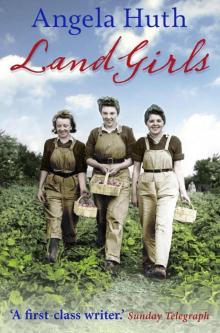

Once a Land Girl Land Girls

Land Girls Colouring In

Colouring In Nowhere Girl

Nowhere Girl Monday Lunch in Fairyland and Other Stories

Monday Lunch in Fairyland and Other Stories Another Kind of Cinderella and Other Stories

Another Kind of Cinderella and Other Stories Invitation to the Married Life

Invitation to the Married Life Easy Silence

Easy Silence